Original concept of Alignment vs Morality in VI·VIII·X

I am well aware of the fact that I have already posted here my thoughts on the explanation of D&D alignments by Gygax in “The Strategic Review” issue 6 (February 1976). I feel however not to be enough complete in my explanation, moreover, I think I should get more in detail about the contents of Gygax’s article and the concept of Morality in VI·VIII·X.

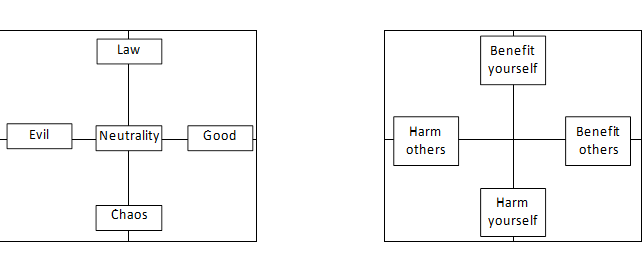

I think it’d be wise to start from a comparison of the two “morality maps”: the D&D one on the left and the one of VI·VIII·X on the right side. One important detail for the reader: the graph on the left here below is not exactly the same of the one in the article, I changed the order of display the axes of the graph to make it comparable to the one I built.

The framework is nearly the same, the main differences are the definitions and the fifth concept of “neutrality”. With reference to the later, I don’t support positions where a never-ending balance is the main driver for any decision; this is, in my view, neutrality: trying to run on the edge of the blade without never falling on one of the sides… this approach is contrary to my vision of ethic: I dislike the solution a neutral character would not be driven by his nature or motivation, it would be defined by the “balanced outcome” he is supposed to look for. And let me add that the solution to avoid neutrality in VI·VIII·X also meets the underlying goal I have in mind for this game: I want to avoid players who takes a position according to a concept of balance which is external to any inner thought. I am sorry if I have made a step into a very sensitive topic which is not strictly related to RPGs but this is absolutely important as one of the goals I have with this game is to outline the importance of moral choices and consistency with character own nature. The game mechanics referred to Morality have been built in a way that avoids behaviors driven by circumstances and rewards those driven by what a person feels insight.

Ok, back to the analysis of the differences: while it is now clear the reason that led me to discard the fifth (and central) definition of neutrality, I want to get into details of the D&D definitions and the ones I used in VI·VIII·X.

Now, an introduction to the D&D definitions: these have different origins; coincidentally, both Gygax and Arneson developed their prototypes with a concept of alignment: while Gygax had been influenced by Tolkien, Arneson’s concepts came from wargames and Diplomacy. In both cases they landed on a 2-axe proposition: good (or law) against evil (or chaos). If you want to have a broad and complete view, I highly recommend this reading. What is relevant for both experiences is that Gygax and Arneson were wargamers and they were used to think with a 2-faction approach: this translates their bias to have a faction against another one in their games. Being a germinal concept, they assumed the same meaning between good and law (as well as evil and chaos). The most outstanding points for this analysis:

- Every character has to pick an alignment, it is not possible to avoid choosing a ‘faction’ simply because every player had to select for which ‘faction’ fighting in the war of Good vs Evil.

- All these alignments are meant as ‘social purpose’ and not the utmost intimate character’s nature: this reflects the fact that D&D was built as a group of characters which interacts against a group – or more – of other characters (namely NPCs) in order to prevail.

- The fight of Good (or Law) against Evil (or Chaos) is systemic and not based on the unique nature of a single character but, at the same time, the game developed from a wide-breath scenario (like the first campaigns/settings of Greyhawk and Blackmoor) into dungeon delving experiences where the dichotomy good/evil lose its significance.

It is clear that Gygax realized that some adjustments were needed for this concept and he wrote the article “The meaning of Law and Chaos in D&D and their relationship to Good and Evil” in The strategic Review #6. In this article, all the points listed here above are still working but it is possible to see a development towards some ideas that are not anymore strictly tied to his ‘wargamer soul’. Later on Gygax developed a model by defining all these terms landing to a 9-fold alignment model which was present in AD&D Players Handbook (1978). And in the AD&D DM Guide (1979) he also added clear definitions of the 9 elements used to define a character’s alignment (whereas in the article for every term he simply listed some words associated to the concept, like chaos = confusion and so forth). In addition these books also report some ‘guidelines’ (apologies, I consider them as guidelines and not rules as they are not precise and concise in their application) based on what he wrote in the article. The most important part of the article is the following:

“Placement of characters upon a graph similar to that in Illustration I is necessary if the dungeon master is to maintain a record of player-character alignment. Initially, each character should be placed squarely on the center point of his alignment, i.e., lawful/good, lawful/evil, etc. The actions of each game week will then be taken into account when determining the current position of each character. Adjustment is perforce often subjective, but as a guide the referee can consider the actions of a given player in light of those characteristics which typify his alignment, and opposed actions can further be weighed with regard to intensity. <…> Alignment does not preclude actions which typify a different alignment, but such actions will necessarily affect the position of the character performing them, and the class or the alignment of the character in question can change due to such actions, unless counter-deeds are performed to balance things. The player-character who continually follows any alignment (save neutrality) to the absolute letter of its definition must eventually move off the chart (Illustration I) and into another plane of existence as indicated.”

This led to the following guideline: the DM has to (secretly) keep track of the character’s actions on the “morality map”.

The approach I used in VI·VIII·X shows significant common points but also others that are quite far from the original concepts of D&D.

The closest one is how to operationally handle the evolution of the alignment: I don’t see any big difference from the rules I set in VI·VIII·X for such a topic. Let me add that I had the luck to be in a mature context of the RPG industry and this helped me to use the original Gygax idea within a set of rules making Morality one of the pillars of some game mechanics. I have made the early guideline a more structured rule which impacts on important aspects of a character like the growth and the divine spell-casting mainly. This is what I proudly see as an integration of this feature within a game system so that even the moral hazard becomes a variable a player has to consider in the decisions for his character. I have already written about this aspect and I won’t go further for the time being (but I am sure I will come back on this topic as I find it essential to a great role-playing experience).

The most distant feature from D&D is about the overall meaning of what an alignment is and, as a consequence, about how this is defined. In this case, I decided to consider the Path in VI·VIII·X as the most inner driver of a character’s behavior. Every sense of ethic and subconscious feeling has origin from the Path. Therefore if a character feels the murder wrong, this is because of his Path. This is diametrically opposed to the concept of ‘social purpose’ in D&D. This gap is nor good neither bad, my choice reflects the will of having a serious role-playing consistent to the ‘true soul’ of the character that the player has defined at his creation. This is also the reason of the definition of the Paths according to the Carlo Cipolla’s model where a clear sense of ethic is outlined (for sure it is raw and not as precise as a 9-fold definition but it comes handy in its simple and clear application). The elements used in VI·VIII·X are less abstract than the D&D ones but they help for sure to define a character by means of a concrete vision of his disposition with ease as the metric used has, to my eyes, very easy and straightforward application. I need however to get confirmation from other GMs and players!

As a conclusion, I know I have already written other posts on Morality and I do apologize if I come back once again: this should let you understand how important I feel this feature in any RPG and the subsequent relevance I gave it in my game. I really hope that you enjoy both this dissertation which starts back in 1976 and the game experience anyone can seize while playing at VI·VIII·X in this regard.

PS kudos to Tom Van Winkle because his post helped me a lot in order to understand the original approach and compare it to what I made up in VI·VIII·X

Comments

Post a Comment